Old School?

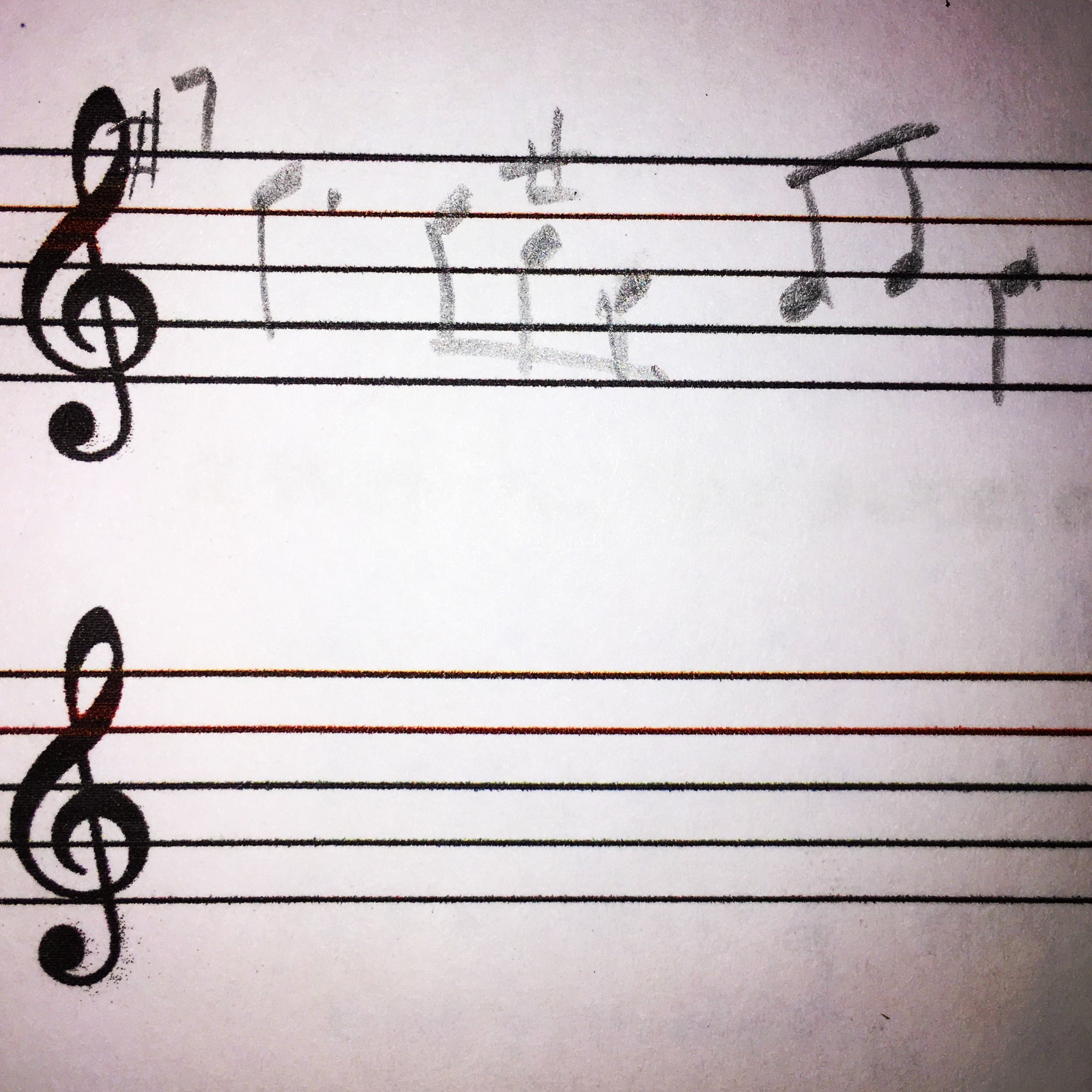

Mixing up my usual composition process tonight. Just me, the piano, and a pencil.

Mixing up my usual composition process tonight. Just me, the piano, and a pencil.

Lots of exciting collaborations and competitions coming up for this beautiful instrument. For tonight, though, it's back to basics with scales, long tones, and etudes.

The Telemann Suite in A Minor for Recorder (Flute) and Strings is a piece I've been playing and listening to for nearly 20 years, and I never get tired of it. When it came across Spotify tonight, I had to share!

A friend and colleague of mine recently gifted me with a real gem of an album, recorded in 1984: Laurie and Baker Play Muczynski. These legendary soloists perform the late 20th-century composer's chamber works for flute and piano, clarinet and piano, and flute and clarinet:

"Time Pieces" for Clarinet & Piano, Op. 43

Six Duos for Flute & Clarinet, Op. 34

Sonata for Flute & Piano, Op. 14

Three Preludes for Unaccompanied Flute, Op. 18

My favorite work on the record (yes, it's actually a record!) is the Duos for Flute and Clarinet. This album is the first recording produced of the Duos in this configuration. The six-movement piece was originally composed for two flutists rather than the flute and clarinet instrumentation heard here. It's not atypical for music for flute duo to be arranged for a flute and clarinet pairing, but what makes this particular arrangement interesting is that Muczynski himself opted to re-arrange his flute duet upon learning that Baker and Lurie would be making this record.

Baker's reputation for exquisite phrasing and an impressive dynamic range in the extreme registers of the instrument really shines in these pieces. His performance holds up 30 years later as an example of truly virtuosic American flute playing.

Curiously, Lurie's performance, while excellent in its own right, doesn't hold up quite as well under modern scrutiny. The two colleagues I spoke with regarding Lurie shared a similar conclusion: Lurie's aesthetic is on the lighter side, embracing a pure core for his sound without exploring much of the darker, warmer timbre that the clarinet is capable of producing. This style of clarinet has largely fallen out of favor, overtaken by powerful, overtone-rich, lush sound.

Still, Baker and Lurie's sounds complement each other beautifully in this recording, where individual lines so often weave in and out of each other that it's difficult to discern where one melody ends and the next begins. They work together expertly to deliver a striking, virtuosic take on these demanding but eminently enjoyable duos.

The entire album is well worth a listen if you can get your hands on a copy of it, a real gem of American composition and performance--and the duos are absolutely worth playing if you can find yourself a duet partner willing to take on the challenge with you.

Image via Pexels.

When my schedule permits, I like to take dance classes. I've tried swing, ballet, tap, and modern and enjoyed them all for every different reasons--much like my love for different genres of music. Dance is hands down my favorite form of exercise, since it combines artistic movement with my beloved music. What better way to take care of my body?

And what better way to introduce some variety into my artistic practice than by exploring a different discipline! Aside from the great workout and enjoyable creative experience, more often than not I leave dance classes with new ideas for things to incorporate into my musical work.

The single most important thing that I walk away with, every single class, is dancers' dedication to the foundations of their art form. In the beginner classes I take, there are a tremendous range of abilities, from true beginner up through local professional dancers. Why are professionals dancing in a beginner class? I wondered for a long time. Then I began to watch them--and their interactions with our teachers--a little more closely.

The beginner classes move slowly, with the opportunity to really focus on each movement and combination as they are presented. For the less experienced, this is a chance to learn for the first time with and form healthy, accurate understanding for future work. For the more experienced? This is their chance to focus on returning to and refining core principles. The teacher may offer a beginner like me corrections on my torso alignment, while offering the professional dancers nuanced correction on the angle of their arms.

It's not unlike a musician's time with slow scales, arpeggios, and tone exercises. When we first start out as beginners, it's our first time learning these concepts. With careful instruction and thoughtful work, we learn them as part of our core musical understanding. As a more advanced artist, we return to them as the foundation of the whole of our work. If we can't play a beautiful Bb scale when the quarter note = 80, we shouldn't be hurrying through intricate Anderson etudes at 132.

Slow, thoughtful, "beginner" exercises give the opportunity to really listen to how we are playing. Are we supporting each note of the scale evenly? Do we produce consistent vibrato throughout the entire compass of that scale? Are we playing evenly? Are we shaping the phrases of the scale? There is so much to be explored by revisiting the basics, no matter what level of musician you are. With "time, patience, and intelligent work" (thank you, Trevor Wye!), it can offer tremendous opportunities for growth.